Before the discovery of insulin, a diagnosis of diabetes was almost a death sentence.

Physicians could do little more than prescribe starvation diets to prolong life by a few months.

The true cause of diabetes remained unclear until 1920, when scientists finally established that the disease stemmed from the inability of the pancreatic islets to produce sufficient insulin.

Yet this understanding alone was not enough—no one had succeeded in extracting the life-saving hormone from pancreatic tissue.

This changed when a young Canadian surgeon, Frederick Banting, proposed a bold new idea. Teaming up with John Macleod, a physiologist at the University of Toronto, Banting outlined a plan that would reshape medical history.

Macleod provided lab space, equipment, and an assistant—Charles Best—setting the stage for a scientific journey marked by setbacks, persistence, and remarkable breakthroughs.

In the summer of 1921, Banting and Best began experimenting on dogs, attempting to isolate insulin from the pancreas. Their tenacity paid off: they succeeded in extracting a crude form of insulin that showed promise in reducing blood sugar levels.

However, translating this discovery into a reliable treatment proved challenging. Early trials failed to sustain diabetic animals for long, and the extract often caused severe side effects.

By November 1921, after countless refinements, they succeeded in maintaining a diabetic dog on their insulin preparation for an unprecedented 70 days, proving that their method held true potential. To improve the extract further, biochemist James Collip joined the group in December, adding his expertise to the rapidly evolving research.

The true test came in January 1922, when fourteen-year-old Leonard Thompson became the first human to receive an insulin injection. The initial attempt lowered his blood sugar, but high ketone levels persisted. Collip intensified his purification efforts, and on January 23, Leonard received a second injection.

This time, the results were remarkable—his blood sugar neared normal levels, marking the dawn of a new era in diabetes care.

The global importance of their work was recognized in January 1923, when Banting, Best, and Collip secured American patents for insulin and its production. In an unparalleled act of selflessness, they sold the patents to the University of Toronto for one dollar, declaring that insulin belonged to the world, not to any individual. As Banting famously said, “Insulin does not belong to me; it belongs to the world.”

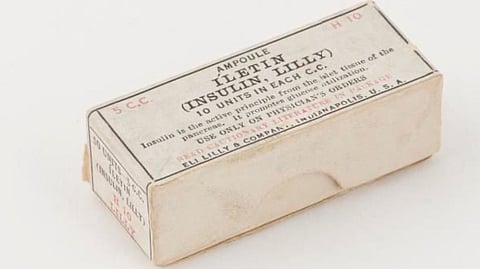

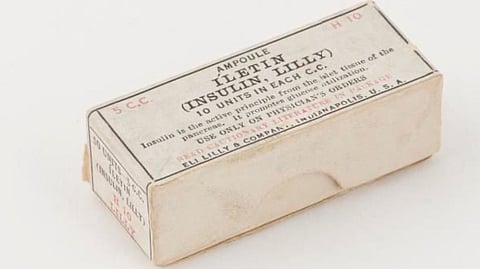

That same year, Eli Lilly became the first company to mass-produce insulin, making it widely available. The Nobel Committee honored Banting and Macleod with the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Reflecting the spirit of collaboration, Banting shared his prize money with Best, while Macleod shared his with Collip.