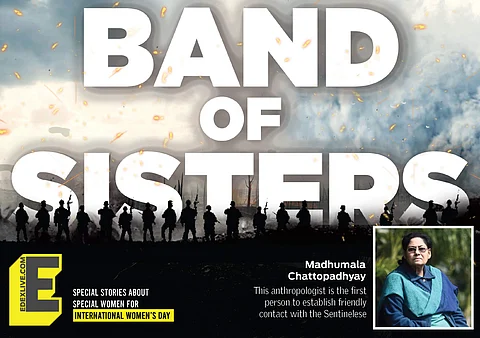

On January 4, 1991, a very determined young anthropologist Dr Madhumala Chattopadhyay saw her lifelong dream come true. As she disembarked the ship and got into a smaller boat and made her way to the shore with a coconut in her hand, her heart raced. She had no idea whether the young Sentinelese man on the other side of the shore would accept her friendly gesture or attack her. This was a historic moment. No one had ever established friendly contact with the Sentinelese, one of the most hostile and most primitive tribes in the world. So as she watched the young man accept her token of friendship, her joy knew no bounds. She had achieved the unthinkable.

As a little girl, Madhumala once came across an article in a Bengali newspaper. It was about a baby born among the Onge tribe in Andaman islands. The article said that there was great celebration because of the birth of this baby. Young Madhumala couldn't understand why it was such a big deal. At the time, her father was an accounts officer with the Southern Railways and they would go on vacation every year to some new place in India. So Madhumala had an idea. She approached her father with the article and told him that she wanted to visit the Onges that year. But she was quickly disappointed as her father informed her it was not allowed for civilians to visit them. The government only allowed certain professionals to visit the area as they were a dwindling population.

That was when Madhumala first decided to choose a profession that would let her see these tribes some day. But as the years passed, she didn't dwell on it too much, until it was time for her to choose an elective for her Bachelor's in Science. One of the options she was given was Anthropology. She had no clue what it was because it was a very rare subject back then. So she went to the library, took a dictionary and learnt what this particular field of study meant exactly. She then approached her professor and asked him the only question that mattered to her - 'Will I be able to visit the Onges if I study this subject'? When the professor answered 'yes', she had no further doubts. This was her calling.

After her studies, she joined the Anthropological Survey of India (ANSI) as a researcher and later as a senior fellow in 1989. The ANSI had seven regional centres and whenever there was a tribal consultation, they would open up centres in that particular tribal region. Now, the Director General was a very honest man and he appreciated talent and passion. So when Madhumala asked him if she could be posted in the Andamans, he told her that he had no qualms about it if her parents would give her permission, as even those who get permanent posting come back almost immediately as it is not an easy station to work in. Luckily, Madumala's parents were supportive and they gave their permission in writing.

She was posted in Port Blair and there were several national projects at that time. She covered the tribes of Andaman and Nicobar islands. But she also had a personal project, she was pursuing her PhD from the University of Calcutta. Madhumala ended up staying in Port Blair for six years, with three-to-four-month stretches on the field, after which she would return to Port Blair to analyse the data. She covered the tribes of the Andamans — Onge, Jarawa, Great Andamanese and Sentinelese, and the tribes of Nicobar islands — Nicobaris and Shompen. Her thesis was focused on the health and the demo-genetic aspect of the tribes. The population of these tribes was so little that if they married outside their tribe, they would lose their genetic identity, and on the other hand, if they continued inbreeding, their population may stay stagnant or even reduce. Her thesis was specifically on children aged 0-6 and their mothers.

Madhumala, 55, recalls her first field visit, "The first time I went to Car Nicobar, the people were very friendly. I spent three months there and tried to learn their language. They would show gestures like 'do you want water?' and I would gesture back. Gradually, I learnt the important words and phrases. Then I came back to Port Blair and analysed the data. The next visit was to the Onge tribe for two months. They were only 100 in number. This tribe knew they were going to become extinct. If you see their genealogy, you can see how they marry within families."

Her next field visit was more challenging — a combined trip to the Jarawas and Sentinelese. It was way back in 1966 when Bakhtawar Singh of the bush police force became the first person to establish friendly contact with the Jarawas, but there was no woman with them. The Britishers had tried but they were not successful. The Sentinelese had never been contacted either. On January 5, 1991, Madhumala became the first woman to do so. She explains, "People told me that it wasn't safe for a woman, but I gave it in writing that if anything happens to me, I would hold myself responsible and won't claim anything from the Government of India. My parents also wrote that they have no objections. A few months before we went, the lieutenant governor's ship had gone to the Sentinelese with a team. They dropped coconuts on the shore and watched from a great distance. So we had the same plan. We anchored our ship very far and watched with binoculars. We could see people with dark brown skin moving. Then we saw some smoke, so we confirmed there was civilisation."

She continues, "Ours was a team of 13 people including crew members, police and a medical officer. We had some gunny bags full of coconuts which we kept on the shore. We then watched what they were doing. They finished all of it and asked us for more. So we decided to open more bags. But this time, we wanted to get closer to them, so we opened it on a smaller boat and started floating the coconuts one by one towards them. A few young boys started touching our boat playfully. Then we got down into the water, but by then our coconuts were over. So we gestured to them asking them to wait and that we would come back. When we came back, one of the boys was pointing an arrow at me. There was a lady behind him. I managed to mutter a few words in Onge language with the assumption that their language was similar and that they would understand. I called out to the lady and asked her to come to me. All of a sudden, the lady diverted the boy's arrow and it fell into the water."

After that, Madhumala and her team established friendly contact. When they decided to visit the Sentinelese again, the authorities decided to send the same team so that they could recognise them. Madhumala wore the same clothes so that they could recognise her better. This time, very surprisingly, they all ran out to the shore from the jungles without any weapons. They even asked for more coconuts. They walked into their boats and took all the gunny bags. They then took the police officer's rifle, but they didn't know it was a weapon. Somehow, the team convinced them to let go of it.

When asked if she believes it is ethical to establish contact with such hostile tribes or whether they should be left alone, Madhumala says, "I'm all for establishing contact with hostile tribes if it is responsible and not manipulative. We should ensure that they are not affected. We should not touch them and spread viruses. As their population is very small, they are very vulnerable. I'm planning to write a book on the dangers and necessary precautions to take. For instance, the Britishers took a Nicobari boy to the mainland, educated him, then they sent him to London where he earned a law degree. Then they sent him back to his community to educate them and translate the Bible. So that way, no one from outside the community went there, there was no way they would be exploited. When outsiders go, they don't understand what's safe for them and what's not. If anyone wants to go for research purposes or if anyone wants to go with good motives, it should be done in consultation with the government, following all the protocols and having a proper team including medical officers, anthropologists and so on. We should only do what's good for these people."

She adds, "There are many people who may want to exploit them or may not be careful enough. There have been instances where the British tried to educate the Great Andamanese people and, in the process, caused an epidemic in their community and a lot of people died. There were also instances where some women were taken out to be educated but came back with venereal diseases that again caused a lot of deaths. The population of 3,000 was reduced to 19. So we have to be really really careful."

Madhumala is also of the opinion that we don't have to try to civilise these tribes. She says, "I don't agree with the common view that we are depriving them of modern technology and civilisation. They have their own technology. For example, the Shompens collect the vomit of a small bird while it is flying and use it as a cure for asthma. They have their own techniques and ways of dealing with problems. There is no point in introducing technology that doesn't suit their ecology. We need to see what they really need and help them with that." Not only are they capable of handling their problems on their own, they are also moral beings. In fact, Madhumala recalls how she never once faced any harassment from the tribal men. "You might think they are primitive, but they are more decent than men in civilised areas. There was never one moment I felt insecure among tribal men. If you treat them respectfully, they treat you back with respect."

Madhumala's years of research resulted in 20 research papers and a book on the tribes of Car Nicobar, which were immediately sent across the world to be taught at universities. When asked why there are not enough women anthropologists, she says, "Anthropology is not an easy field for women because you need to spend long periods of time on the field and you're constantly travelling. I am single, so I've not had to give up much, but when you have kids, it's a really difficult job to do. It's also physically demanding as a lot of the times, I've had to stay without proper food or water or sanitation facilities. I would lose around 12 kg whenever I was on the field. My blood pressure would get very low too."

Madhumala's rare contribution to the field of anthropology got her many high profile opportunities in universities abroad. But she had to reject the offers to take care of her family. She now resides in New Delhi and works as the Joint Director of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.