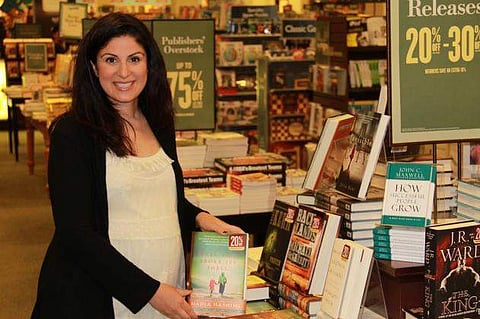

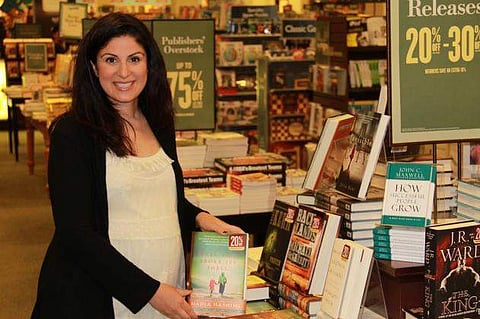

An American paediatrician of Afghan origin, born to Muslim parents and currently running as a Democratic congressional candidate for the United States House of Representatives. Did that sound like an oxymoron to you, given how things stand in the White House? Then, you definitely haven't heard of Nadia Hashimi. Author of a few bestsellers including The Pearl that Broke Its Shell, hers is among the strongest voices that both countries — USA and Afghanistan need right now.

The existing atmosphere of terror and fear in Afghanistan is, of course, worrisome, but with her pen, this 40-year-old is quite sanguine about changing the current scenario. Thrilled about her first visit to India to attend the Neev Literature Festival 2018 in Bengaluru, she spared a few minutes to talk to us about being an Afghan-origin student in New York during the 9/11 attacks, rising Islamophobia under the Trump regime and of course her books and the story behind them.

Excerpts from the conversation:

What was your inspiration to write The Pearl that Broke Its Shell?

In 1996, I had just graduated high school and was packing my bags for four years at a university. I had ambitions of becoming a physician and knew that everything was within reach. That same year, the Taliban took official control in Afghanistan. While I studied chemistry, girls in Afghanistan were told they were neither capable nor worthy of elementary education. It boggled my mind that such a misogynistic regime could take control of the same country where my mother had become a civil engineer. The injustices suffered by women and girls in Afghanistan lit a fire in me. I wanted to share their stories with the world so that people would know the burdens faced by the girls of my generation who had to live under such rule.

For an Afghan who grew up in the US, have you faced any sort of difficulties?

I was a first-year medical student in New York City on 9/11. My apartment and campus were not far from where the Twin Towers stood. That catastrophic event divided my Afghan-American life into a before and after. In the days that followed, while Americans grappled with the unknown feeling of being attacked in our own backyard, a wave of hostility erupted towards those associated with Afghanistan or that region of the world. Someone, under cover of night, threw a rock at the window of my parents’ store. Two men shouted hot, angry words at me and my fellow olive-skinned classmates as we walked home from class. But my experiences were mild in comparison to so many others. In today’s United States, however, we have experienced a reigniting of some of those ugly sentiments. Donald Trump has given near carte blanche to xenophobia and Islamophobia. Since running (unsuccessfully) for US Congress last year, I’ve been privy to some of the darkness, people feel comfortable unleashing online. But, again, there is space and tolerance for my identity in the US because Americans continue to insist on our foundational values.

What is the biggest threat faced by Afghanistan right now?

Extremism remains the biggest threat to peace in Afghanistan today. While the Taliban were officially ousted from control in 2001, they have remained in the country. The group continues to undermine the authority of the central government and, thereby, democratic rule. They have continued to oppose involving women as equals in society and law and they have perpetuated sectarian violence. So long as women, minorities and journalists continue to be oppressed or murdered, there will be no peace.

So much has been written about Afghanistan in English fiction. But do you think it has made a change in the situation of common people there?

As a reader, I know very well the change-making power of fiction. I’ve felt the impact of stories on my own being and have the privilege of receiving moving emails from people who have been affected by my work. These stories have led some readers to inquire what they can do to help the women or children of Afghanistan. Showing readers the many reasons we have to believe in a positive future for the country is one small part of creating a global network to cheer on this nation. The true agents of change are those Afghans who wake up day after troubled day and work towards a bright future for the country through their work as teachers, engineers, students, attorneys, physicians, parents and more. In exchange for the inspiration they give me, I can only hope to honor them by sharing their stories of tragedy and triumph.

What were your biggest fears when you visited Afghanistan?

When I visited Afghanistan in 2003, I was in my early twenties and likely still carried a hint of that adolescent invincibility. Kabul was, perhaps similarly, at its most secure with the heavy presence of NATO forces. Apart from my fear of flying on a small aircraft, my trip was not made with apprehension. Landing in Kabul, my parents and I were greeted by a small crowd with outstretched arms. I had relatives from both sides still living in the country.

Visiting the schools, hospital and bustling markets gave me a sense of the bold energy driving reconstruction and growth in the nation. Seeing the smiles on the faces of schoolchildren early in the morning – boys and girls – made my heart swell. I feel more trepidation from a distance, as deadly violence wracks the country with disheartening frequency.

What could be the solution to the problems there?

There is no single solution to Afghanistan’s woes but it’s evident the best remedies must come from within. Afghan people must be in the driver’s seat when it comes to nation building, an ongoing process. Solutions applied from the western world will most certainly not fit in this nation. The prolonged need for US presence in Afghanistan is in part due to a lack of understanding of this simple point.

(Nadia Hashimi will be one among the speakers at the Neev Literature Festival 2018, on September 27, 28 and 29 at Neev Academy Campus, Yemalur, Bengaluru)