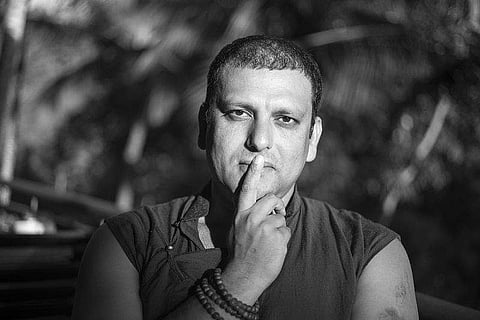

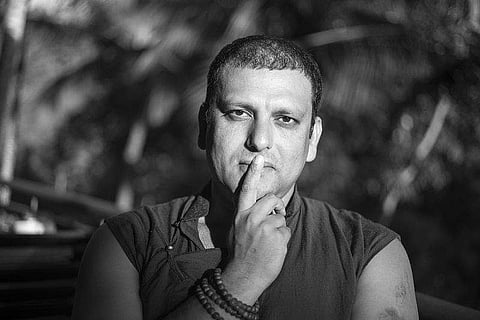

He has a certain glow that you can't miss. Or ignore. Some might say it's because he has been leading a sedentary, monastic lifestyle from when he was just 10, some might say it's because he is a learned man. Or it's also probably because you get less tanned in America. Whichever way it is, when you're a monk who's studied at Harvard and runs the Dalai Lama Center at MIT, like Tenzin Priyadarshi, there's no question of dismissing him lightly. This was my first face-to-face interview on video and I told him that, "We'll try not to make you nervous," he laughed. I was confident that I was comfortable with the well-built, good-looking man who had serene poise. We spoke about media and AI, where I studied, my roots back in Kolkata and whether the city has changed much.

Then the camera was on and I was clueless about what to ask. Priyadarshi, who was in Chennai to announce their new collaboration with Krea University, smiled at me and sort of gave me the courage to stagger on with the conversation. I couldn't finish half my sentences. He did not wait for me to try and embarrass myself any further and answered promptly. Excerpts from the most comfortable stammering conversation ever:

Both as head of the Dalai Lama Centre as well as through your deep personal relationship with the Dalai Lama over the years, tell us three lessons that you learnt from him that have changed your life

I would say, first, a sense of curiosity. He has been a very curious individual who engages with all forms of intellectual discussions not attached to a belief system particularly. The second thing is a sense of humour. Sometimes, we forget how important humour is to maintain sanity in civic society. We tend to take things too seriously. The third thing is compassion. The idea that, if humanity has to survive, compassion needs to be at the core of whatever drives us to manifest what we are looking for.

You've spoken about following a discipline in non-violence and that it should not come from a place of anger or fear but should be strategic. But how do you think the issue of Tibet's autonomy can be resolved peacefully and non-violently after almost 60 years of struggle? What would you like to tell the Tibetan youth?

We all know that change doesn't happen overnight. It requires a lot of perseverance. All I can recommend is that they practice fearlessness and practice perseverance. Sometimes the change doesn't happen in the time frame that we want it to happen or the mode that you want it in. We will see how it all turns out, but having a sense of perseverance and clarity is a good thing.

There is an increasing number of cases of violence and intolerance in campuses. Aren't these people being provided with the education that also teaches them to rationalise events and not follow fanaticism?

I think the key thing to ask is what type of culture is prompting such actions. There should be some roles given to the students along with the faculty to deeply think about how to reorient the culture of the institute. We have gotten used to the idea where we have a system and we sort of perpetuate the system without actually examining it. We are at a stage where universities need to exercise critical thinking. There are certain systems we have inherited that we need to refine and carry forward. And there are some outdated ones that should not be continuing. We need to manage it in a way that we do not perpetuate a toxic system.

Tell us a bit about your journey. We've heard you say that the Dalai Lama's influence on you started very early. What was that like?

I don't think my journey is out of the ordinary. It's just that the things that drove me in my life were a sense of curiosity and a sense of fearlessness. It just so happened that I took on a religious monastic lifestyle very early on but I still had an interest in science and technology and I went on to explore that. My mind has never been settled on one discipline. I believe in a sort of anti-disciplinary nature of education. Much of my work today is reflective of that journey where I am able to sentisise and integrate the learning from different aspects of my life.

Given your years of travelling to some of the top universities in the world - Harvard, MIT and many more - and teaching and lecturing on peace and conflict resolution, what do you believe Indian students needs to be learning in schools and colleges today?

I think, in general, Indians are doing quite well if you look at most of the complex companies the Indians are heading right now. So, I think there is some merit to the type of education being imparted here. But I do believe that there needs to be more emphasis on some kind of ethical learning that allows individuals to think about how to become good participating citizens. Most Indian institutions have been driven by the idea that you go to a university mostly to get employed. I think the landscape is changing today in a manner that we can talk about leadership and the idea that most people should be nurturing leadership abilities.

With the advancement in technology and its application in the field of education, how should we restructure or rethink the current education system that we have?

I think the change is going to be huge. It's going to change the landscape of job markets. Universities need to think what is relevant in this era of changing employment landscapes. Otherwise, we might be imparting education that might get outdated in the next five years. I think it is an opportunity for universities to be creative. It's both exciting and terrifying at the same time because there are a lot of unknown variables.

How do you think we are being affected by the transformation that technology and AI is exposing us to?

The new designs in technology should be driven by some level of ethics and empathy so that it does not have any detrimental impact on society. But we are seeing constant behavioural changes with the use of even mobiles in terms of how we interact with each other. It's a question of how much screen time versus face time.