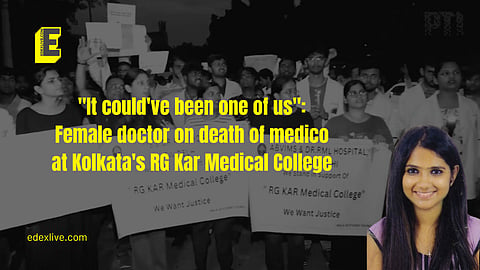

The first thing I saw this morning was the news that a fellow doctor at RG Kar Medical College, Kolkata, had been brutally raped and murdered. The chest medicine postgraduate student was on a gruelling 36-hour duty in the emergency medicine building.

With no duty doctor’s room available, she found a seminar room on the third floor to sleep. Hours later, she was found — bloodied, brutalised, and no longer breathing.

The news stopped me in my tracks, not just because of the horrendous nature of the crime but because, as every female doctor would have realised by now, it could've been us.

I remember the time I was working in a secondary hospital in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh. We used to get critically ill patients all the time, and sometimes, they were too ill to be managed in our hospital.

At that time, the doctor on duty accompanied the patients and their relatives to a tertiary centre in Vellore. I recall those ambulance rides — no nurse or EMT to support me, at all odd hours of the night.

On a few nights, I would be the only female in that vehicle — along with the driver, the patient, and male relatives. I look back and wonder why I put myself through such risks.

Was it because my male colleagues were vocal about the need to pull my weight? They made it clear that I couldn’t be the weakest link, burdening others by asking to be exempt from these night transfers.

I also remember a female colleague whose family refused to let her go on these transfers and spoke to the hospital administration about the same. The way it affected her reputation — as someone flashing her female victim card to avoid duties — must have scared me, too. Subconsciously, I knew I didn’t want to be perceived like that.

With time and distance, I wonder if it is anyone’s fault.

My colleague was justified in feeling uncomfortable travelling at night with strangers. In hindsight, I am glad she and her family raised the issue with the administration.

But should a male doctor also have to accompany a patient alone in an ambulance? In an emergency, one person cannot stabilise a patient, manage machines, and administer medications. Shouldn't the hospital have teams trained for these transfers?

Why did none of us ask for the help we so clearly needed?

Medicine has long embraced a "suck-it-up-and-work" mentality. I’ve seen colleagues shamed for taking sick days, eating meals, and even sleeping.

Resident doctors often resign themselves to lousy infrastructure, dismal staffing, and being treated like slaves by faculty.

Seniors expect PG medical residents to work as if facilities are not limited. If they cannot do something due to systemic issues, they are shamed for lacking the strength to circumvent these problems.

Given this, could the deceased doctor have even mentioned the lack of a duty doctor’s room without being labelled lazy for wanting to sleep? I find it ironic when doctors push back against patients for expecting superhuman feats from us, given that we expect the same from each other.

India has become a hotspot for violence against doctors, with junior and female doctors particularly vulnerable. As the deceased medico’s case tragically shows, the violence against female doctors often takes a sexual turn.

As the investigation proceeds, I fear the narrative will shift to discussing women as liabilities in the workforce rather than addressing the systemic failures that allowed this tragedy.

There needs to be an attitude shift in how we view doctors' problems, both within and outside the community.

We are not weak for asking for better working conditions, shorter hours, more security, or at least a duty doctor’s room to rest during inhumane shifts.

(Dr Christianez Ratna Kiruba is a 29-year-old internal medicine doctor, freelance health journalist and Deputy Editor at Nivarana, India's first public health digital platform. She is an intersectional feminist and part of the LGBTQIA community. She is interested in viewing public health issues through the gender lens.)