The ecosystem that surrounds us forms the very foundation of life on Earth. Yet, despite its vital role, human actions increasingly undermine the balance and sustainability of this delicate system. Rapid development, unchecked exploitation of natural resources, and indifference toward ecological limits have placed immense strain on the environment. In this context, ecologists emerge as crucial voices reminding society of the intrinsic value of the ecosystems that sustain human existence.

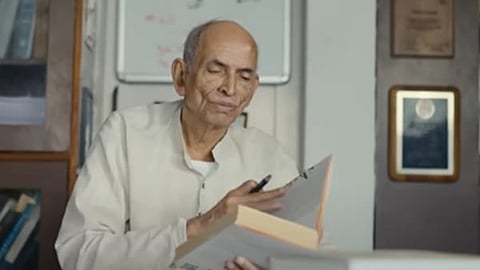

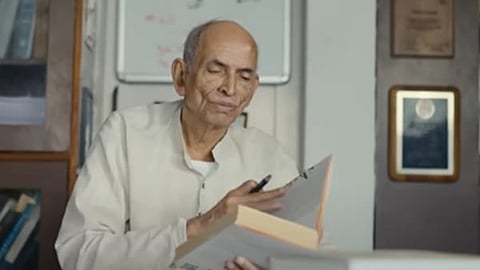

In India, discussions on ecology inevitably bring to mind the name Madhav Dhananjaya Gadgil, or Madhav Gadgil. His lifelong contributions to environmental science and conservation have not only shaped India’s ecological discourse but also served as a powerful reminder of the consequences of human interference in natural systems. His death on January 7, 2026, marked the loss of one of the country’s most influential environmental thinkers, someone who fundamentally reshaped how India understands conservation, development, and democracy. Among his many contributions, none has sparked as much debate or retained as much relevance as the Gadgil Report, formally known as the report of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP).

Gadgil was a founding director of the Centre for Ecological Sciences at the Indian Institute of Science and a lifelong advocate of participatory environmental governance. He consistently argued that ecological protection must be rooted in scientific evidence while remaining responsive to local realities. For Gadgil, conservation imposed through top-down policies without community involvement was not only unjust, but ineffective.

This philosophy was most clearly articulated in the Gadgil Report. In 2010, the Ministry of Environment and Forests constituted the WGEEP under Gadgil’s leadership to assess the ecological health of the Western Ghats, a UNESCO-recognised biodiversity hotspot that plays a crucial role in climate regulation, water security, and livelihoods across peninsular India. Submitted in August 2011, the report presented a comprehensive, science-based assessment of the region’s ecological sensitivity.

Using geospatial mapping and ecological indicators, the panel classified the Western Ghats into different zones based on their vulnerability. It identified critical wildlife corridors, biodiversity-rich regions, and ecologically fragile landscapes, while warning against unregulated mining, quarrying, large-scale construction, deforestation, and poorly planned infrastructure projects. Crucially, the report did not advocate blanket restrictions. Instead, it proposed graded regulation, allowing development where ecological risks were lower and calling for stricter protection where damage would be irreversible.

What distinguished the Gadgil Report from earlier conservation efforts was its emphasis on democratic decentralisation. It recommended empowering local self-governments like panchayats and municipalities to play a central role in environmental decision-making. Gadgil believed that communities living closest to nature possessed valuable ecological knowledge and had the greatest stake in sustainable management.

Despite its scientific rigour, the report faced strong opposition, particularly in Kerala. Farming and settler communities in regions such as Wayanad feared that ecological zoning would threaten land rights and livelihoods. These concerns were shaped by complex historical and socio-economic factors, including migration into forested areas during the 20th century. Critics argued that while the report was environmentally sound, it insufficiently addressed the everyday insecurities of people dependent on the land.

Over a decade later, however, the warnings outlined in the Gadgil Report appear strikingly prescient. The Western Ghats have witnessed repeated landslides, extreme rainfall events, floods, groundwater depletion, and loss of forest cover. Many of the very risks identified by the WGEEP, including unregulated construction, mining, hill cutting, and ecological fragmentation, are now directly linked to recurring environmental disasters in the region.

In this light, the Gadgil Report is increasingly viewed as a foundational framework for balancing ecological protection with sustainable development. Citizen-led initiatives to revive its data and recommendations signal a renewed recognition of its value. The report’s core message has only grown more urgent in the face of climate change: that development must operate within ecological limits and democratic structures.