‘A holistic and multidisciplinary education, as described so beautifully in India’s past, is indeed what is needed for the education of India to lead the country into the 21st century and the fourth industrial revolution’ — This is what the New Education Policy says under its proposals for transformation of Higher Education in India. The drafters go on to mention ‘the ancient Indian’ universities Takshashila, Nalanda, Vikramshila which had thousands of students from India and the world studying in. In the final draft of the NEP, the government states that it wants to gradually phase out the system of ‘affiliated colleges’ over a period of 15 years through a system of graded autonomy. The policy’s main ‘thrust’, the Centre has said, is to end the fragmentation of higher education by transforming higher education institutions into large multidisciplinary universities, college and Higher Educational Institution clusters, each which will have to have 3000 or more students.

If colleges are unable to have a strength of 3000 by 2030 and become multidisciplinary institutions, then they will be merged with a University.

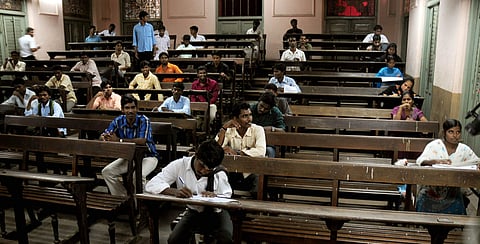

While on a superficial level, the NEP’s suggestions can seem harmless, advanced and even progressive, on the ground level there is a fear of what will happen to students who study in small colleges, the teaching and non-teaching staff and even the building. How will small colleges manage to get 3000 students and how will they be able to get to this supposed high standard of teaching and offer multidisciplinary courses when they don’t have the resources or the money? Who funds them, who determines their worth? We spoke to the principals and professors of some government colleges across Tamil Nadu to find out what they think about the NEP’s prescriptions in this aspect and what their worries are. The professors were only willing to speak to us under the condition of anonymity as they were worried they might be penalised or targeted for speaking to the media.

The institutions which will probably face the worst impact of such a proposal are colleges situated in rural areas. The NEP suggested a similar solution to single teacher and schools with a low number of children — merging them into school complexes. With both these solutions, there is one major problem — cutting off access. Both educators and activists with decades of experience working with small schools/colleges and in remote areas know that they are the sole source of education for children in the area. The farther the source, the fewer students will appear in the classrooms. One of the people we spoke to, the person in charge at a college in Sivakasi says it's ironic that the NEP cites this solution as a method to decrease dropout rates, “How is moving an institution to a farther area going to ensure lower dropout rates. Logically speaking, it is only going to increase. I can’t get my head around it, if you cut off the opportunity for a candidate to go to a nearby college, how can you expect that the dropout rates will not increase?” he asks. There is already a disparity between students from privileged and underprivileged backgrounds, rural and urban.

How can I increase the number of children residing in a village, asks a professor of a Kanyakumari college. “Say there are 100 children residing in a village, only a 100 can turn up at my college. In another village maybe there are 1000, or maybe there are 50. But our job is to provide an education to these students, right? You can’t compare one village to another and you can’t compare one college to another based on the strength,” he asserts.

Most of the students who come to the Sivakasi college are children of construction and print workers, “These parents send their children here because it is close by, none of them would think about sending their children to far away campuses,” the associate professor said. “Just in my department, there are two ST girls who travel 35 kilometres to come to college. This itself is a long journey for them but because it is a government institution, the parents send them. Now if something like this proposal gets implemented, the parents will prefer the students stay home.”

A teacher from a college in Salem points out that these colleges exist because in order to reach out to those who have no other access. “Even now in our college we have students from Yercaud, they have to come all the way down here to attend college. We were, in fact, discussing how it would help to have a college up there. Travel makes us also sick while going up and down the hill. Many students have also told us this. When this is the case, it makes no sense to shut down colleges if they don’t have 3000 students by 2030,” she said.

The Salem professor points out another very interesting fact that the drafting committee might have overlooked — over the last few years, more and more colleges have been set up in rural areas — “Kangeyam in Tirupur district, Pennagaram, Thiruvandram, Sankarankovil, Surandai and several other small towns in the state. All these colleges are new and it's good because it is beneficial to the people living in these areas,” she lists. Another fact that the educationist tells us is that while people complain that some government schools in remote areas have very few children who have enrolled, the case isn’t the same with colleges in small towns, “Most of these colleges will have high enrollments because the education is affordable. They always have good strengths.”

“In a post COVID-19 world, it has been predicted that there will be 24 million dropouts worldwide. On top of that if policies like these are brought in, then more students will prefer to not pursue academics,” a professor says. If they don’t have a government college in the vicinity, then most students will be forced to get themselves admitted in self-financing, private colleges near their home. “Most students come to government colleges because they can’t afford the education and they can be assured of a good education here. If they have to join private institutions, there will be a huge burden on their families to pay the fees, and these are the families that deserve to get an affordable education. If the colleges only end up being in the cities, then only the well to do kids will have a good education,” he adds. “The colleges also have the liberty to fix their own fees and so parents will be paying purely for accessibility,” another professor points out.

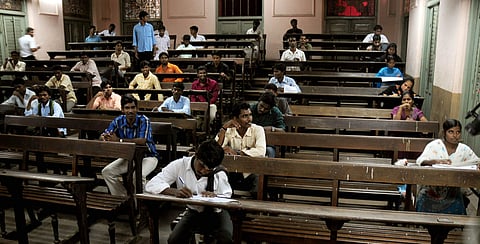

The section to be affected most in rural areas are — women. Women’s only colleges especially will take a huge hit if this policy is implemented, the educationists feel. Dr V Ravi from the All India Federation of University and College Teachers’ Association said, “If ladies-only colleges are forced to merge with Universities, then parents will simply not allow the women to go to college. Primarily because it will be co-education and second, the long travel.”

“It is a safety issue too. See, for example, if you mention my college’s name everyone in the town knows it. They’ll tell you exactly where it is. So when everyone knows a place, they can trust it more. If they have to send their ward to an area that they are unfamiliar with, they get worried. Long bus rides are also not an option that the parents appreciate,” the Kanyakumari profesor tells us.

A professor of a women’s college in Western Tamil Nadu tells us that most of the women on campus are first generation learners and a huge margin of the women students are married. The students marry after they finish their twelfth standard and then join college for higher education. “Since they come from rural areas where daughters are pushed to marry early, they only apply for higher education after they are married. Now that the college is only 10 or 15 kilometres away, the families don’t mind sending the students. So if colleges are only available 30-40 kilometres away, then these women will not be able to travel far to attend classes as they have to manage their families as well. Thus drop outs will increase,” she added. A lot of these students also have part-time jobs, the academician says, “Since the college is close by, they are able to manage travel. Now if they have to travel to a college far away, then most of the time they’ll be travelling and reach home late. We have to understand that these women are coming out of their homes for the first time, so we have to make the access as easy as possible.”

The reasons keep stacking up. “Looking for a hostel, looking for accommodation outside the campus, all this is an extra burden. And with boys, it's easier. They’ll hitch a ride, get on a crowded bus and get to class. But it isn't the same for the girls. They can’t just hitchhike and come to class,” the Salem educator says. The senior professor says she regularly interacts with students and has asked many why they choose to go to private colleges even if there is a government college just a little farther away, “They all have just one reason — college buses. The private colleges today have a fleet of buses and they go to the remotest of areas and pick up students, right to the doorstep, through any rickety road. Despite it costing a bomb, parents sell their lands too to be able to afford the fees and the buses. So this policy, if implemented, will only help private institutes profit. All they need is a fleet of buses. I ask them if they can’t just take a town bus but many girls haven’t travelled alone before and their parents worry about their safety, so they would rather let their daughter take a bus that comes to their doorstep then send them to the town bus stand,” the Salem academician explained.

The women’s college teacher points out that for all the demand for better quality of education and top class infrastructure, there are still basic problems like unhygienic toilets that students are still faced with, “Many students even tell me they prefer private colleges because there are no clean toilet facilities in government institutions sometimes. Now for 3000 students can we ensure that there will at least be 30 toilets?” she asks.

On paper, the NEP seems perfect, but only for urban institutes, the educationists feel. “Rural Colleges already miss out on so many funds because people are unaware sometimes. The NEP demands that there be 120 teachers, multidisciplinary courses. In my college we are just 10 teachers for the entire college, the others are all guest lecturers. How are these teachers supposed to take on so much work, they are already an overworked lot. They are saying if we don’t show output, they’ll shut us down. How in the world can they expect that kind of output from a rural college on par with a self financing college without the same sort of infrastructure?” the Women’s college professor asks. She worries that these policies could result in a lot of ‘broker’ universities that will only rip off desperate students.

The Kanyakumari teacher says that through this policy, the government wants to commercialise education and wash their hands off from funding public education. “They are not ready to spend their money on public funded colleges. They are essentially telling private institutions to design their own courses, curriculum, charge their own fees, pay their staff, give their own certificates,” he feels.

The professor also feel that the NEP is very vague in the way that it has framed these policies and doesn’t really define what it means or plans to implement it. “The NEP doesn’t say what will happen to the building where the college has been functioning. Will students continue there or be sent to the University it is merged with? What will happen to the staff? Will they all be jobless? What about the money that was invested into building that campus?” another professor asks.

There are also policies that the NEP describes that are vague, especially with regard to the multidisciplinary move, the Kanyakumari professor feels. “There is no definition, no answers. The terms that have been used are also very vague. Is the staff supposed to generate their own fund? In a rural setup how much is even possible? The NEP also seems to suggest that there won’t be academic councils — a space for teachers, principals and administrators to debate, discuss and decide. Already even here we can’t get a word in but in some cases we get together and even shape a proposal to help better it. Now the government is saying there will be an external team that will decide these matters and this team will invariably end up with members who are ‘big’, industrialists and such and they will take matters into their hands. Now the rule is that if an assistant professor completes 12 years, they will be made associate professor. Now if a person on the committee doesn’t like the candidate, what guarantee that they’ll get the promotion,” he questioned. Career advancement ends there, he adds.

“It is the teachers who are on the ground, who know the reality. If teacher representation is not there, there is no way that a college and its students can progress. Having a syndicate with people who have vested interests is only going to worsen the administration,” the Sivakasi professor adds. “Nobody is against any policy that is going to make the academic experience better for students. If they think certain courses will make the students well rounded, we are going to support that. But you have to tell us exactly what you mean and how we are supposed to do it. But nobody knows better than the teachers what the ground reality is and I’m glad now that the Centre is asking for suggestions,” the other professor adds.

“But it isn’t like the Centre doesn’t know,” another teacher tells us, “We have been sending letters, staging protests, seeking answers. They very well know what our stand is but they are failing to make these processes transparent,” he feels.

One of the teachers says that she believes the government should be doing the opposite of what it is doing now, “In fact, I think that the government should be building more colleges in the remotest of areas, in every rural town. The more colleges are built, the more students get an education. That is when the gross enrollment will increase, not by merging or shutting down colleges. At least students from a couple of villages should be in the vicinity of the college, that to me makes more sense.

The Dharmapuri educationist stresses that it is important that education comes back to the State List, the evidence to prove why she is right, is in the NEP, she points out. “ When you look at it, you feel like they are only talking about the institutes in the cities. Cities across the country might have similarities, but the rural landscape is diverse in every state. In UP, it's different and in Tamil Nadu, it is different, only the state government will be able to comprehend the rural landscape. Now, it seems like the NEP has been framed only considering certain regions in the country. Rural areas and urban areas even within a state are so vastly different, so how can one have a blanket policy for the whole country?”

Despite the beauty of India’s past the cruel reality is that large sections of society did not ever make into the large gates of the education systems then. Is that the past that we want to revive?