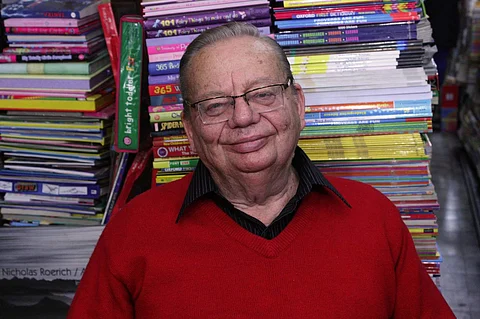

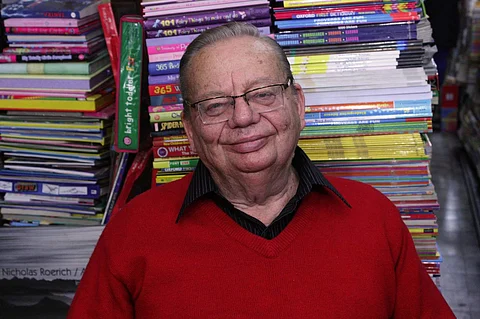

Coughing sporadically, Ruskin Bond cautions us about his haunted landline. “There is a ghost in it, a very mischievous one who interrupts and cuts the line often,” he says conspirationally, adding that he is yet to write about it. It’s a shade past 6 pm and while we’re half a country away from chilly Mussoorie, it seems perfectly natural to imagine the legendary author, who was recently conferred the Padma Bhushan, smiling away to himself at his private joke.

While we may have to wait for the story of Bond’s haunted landline, his new collection of short stories — Whispers in the Dark, is already out on bookshelves. This book of spooks has 35 short, crisp tales, all of which send all sorts of chills down your spine. Whether it’s the slighted wife Gulabi, who is now and then seen throwing herself into the river Gangotri or Michael, the boy-turned-ghost, who met his end far too soon and is occasionally spotted on his cycle whistling to himself — all stories, though with no common theme, have eerie characters which pique our curiosity. There is indeed no one better than Bond at introducing children to the distinctive beauty of the hills with its idiosyncratic people from Rusty (The Room on the Roof) to Binya (The Blue Umbrella), add to this a plethora of ghosts every now and then (Ghost Stories from the Raj, A Season of Ghosts). After all, he’s been doing it for six decades, and he doesn’t seem to be tiring any.

First encounters

As his parents were not particularly spooky-minded, the first horror tale he came across was in the book The Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by MR James. Having been brought up on a healthy diet of ghost stories by other classical writers like Algernon Blackwood and Walter de la Mare, the author thinks that the secret to their success was the creation of the right spooky atmosphere in their stories.

What better place than India for this, where there is no dearth of ghosts or their stories.Bond, jovially of course, says that supernatural creatures are also a tourist attraction for the thrill-seeking bunch who visit haunted places for chills. In fact, not so long ago, someone in Mussoorie asked him if he could write a story which introduces ghosts in their hotel to boost their check-ins.“I promised that if they let me stay there free for a month, I certainly would,” he says laughing.

Come to think of it, India is inhabited by its own indigenous variety of ghosts like prets, churels and jinns and as per Bond, a few British ghosts as well. “The Brits went away in 1947 but they left a lot of ghosts behind in hill stations and old cantonment areas where one sees the old colonel on his horse or Memsaab bopping around without her head,” says the author, almost seriously. That’s when Bond lets us in on another little secret that comes across as crowning irony. Bond doesn’t believe in ghosts though he can always “cook up a ghost”. Perhaps it’s showing.

He tells us about a complaint he once got from a little girl that the ghosts he whips up, albeit good, aren’t frightening enough. “She asked me if I could make them more scary and I said that I’d try,” he says, admitting that, “to use words in order to stimulate suspense or fear is quite a challenge,” especially in this age of horror movies and serials that children are exposed to.

Right on cue, the ghost residing in his phone cuts the call.

Thankfully, the ghost in the phone line doesn’t seem to have any hang-ups about us resuming the call and so the balance is restored quickly enough.

Vague distinctions

“Often, the books I write for the general reader end up being classified as children’s books or find their way into school curriculum and the books I write for children end up being read by adults. I think the line is not very distinct. Also, I wouldn’t like to be restricted as a writer for children,” says Bond after we reconnect and he apologises for his bad throat, adding that half of what he has written is for young readers while the other half is for general readers. We agree that he shouldn’t be bound by any genre, for he has written all kinds of stories, for all ages, “I’ve been writing stories for over 60 years now, I had the time to try out different genres,” says the Kasauli-born writer. As the only book publishers in the 1950s were ones for school textbooks (“That’s why Indian authors of the period would get published abroad, if they were any good”), he had to resort to freelancing for newspapers and magazines. “The pay was good back then, ranging from rupees 50-100, which went further in those days than it does now,” he recalls.

Looking back, he says that his writing style hasn’t changed a great deal. “Maybe I am a little more cynical now, compared to my more romantic inclinations when I was younger,” he says, calling his writing “uncomplicated and simple” and as a result, “whether writing for children or adults, there is no great difference in my approach.”

He’s delightfully old school. In an age when the computer is king, Bond prefers to write by hand, directly on the pad because “I have visualised the story in my head already, so it’s only about putting it into words and making it interesting,” says Bond, crediting this method for warding off any possible writer’s block.

The 82-year-old author draws his stories from memories of the bygone times, after all “the past is always with us for it feeds the present,” he says, quoting himself. The past along with wisdom and memories brings the realisation that learning is a never-ending process. Maybe that’s why he is currently reading the Oxford English dictionary, learning the meaning of new words and origins of the old. “I am sort of trying to improve my language,” says the master storyteller, whose words have charmed us all as children and continue to do so till date.

At the end we thank him for talking to us despite his bad throat (“not at all, nothing a little cough syrup and some hot rum can’t cure”) and the ghost residing in his phone, who mercifully refrained from cutting our conversation again.

BOND'S GUIDE TO INDIAN GHOSTS

Prets or bhoots: These are your regular, run-of-the-mill spirits of dead men, made immortal as they dwell on Earth searching for only they know what.

Churel: The ghost-woman covered with hair and ears of an ape, is full of animosity towards men probably because, in life, she was mistreated by them. To recognise one look at her feet, which in all probability will be turned backwards and have toes which are three feet in length.

Pisach: This ghost is a malignant, sometimes amorous one. It has no body or shape. It is known to dwell in graveyards or peepal trees.

Munjia: This is the disembodied spirit of a Brahmin youth who passed away before his marriage. Snap your fingers in front of your mouth while yawning under a peepal tree or a munjia will take over your body.