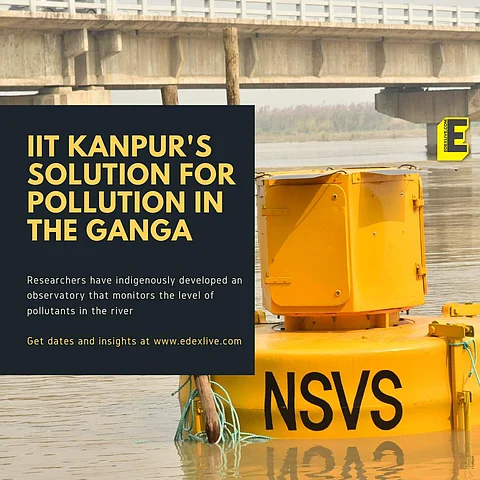

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur (IIT K) have developed an Aquatic Autonomous Observatory named Niracara Svayamsasita VedhShala (NSVS) to monitor the pollutants in River Ganga in real-time. Led by Principal Investigator Prof Bishakh Bhattacharya from IIT Kanpur, the team built an observatory on a buoy in the river, which is equipped with four indigenous sensors that can detect various types and levels of pollutants in the river. The project was funded jointly by the Central Government and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's (MIT) Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

Between heritage and histrionics, the Ganga river's claim to attention is unarguable. It is a polluted, revered body of water that has sustained generations and provided them with a final resting place. It swallows prayers, ashes and trash and is a veritable deity in its own right. Cleaning the river has been more of a political agenda than a practical one. It takes knowledge and effort rooted in technology and science and conscience — something that struck Prof Bishakh during a rather somber, personal visit to the river to release the ashes of his deceased father. That is when the need to understand how polluted the river exactly is struck him and he set out to find takers for his ideas of manufacturing sensors that can detect pollutants specific to the ecosystem in India.

"It is important to have distributed observatory in critical rivers in India. There is no such product available in India currently. If we import, the cost becomes prohibitively high. Such technology exists only on River Mississippi in the United States and it costs Rs 50 lakh. And apart from that, there is also the cost of security for the expensive, imported technology, which can make a dent of Rs 3-4 lakh per observatory on the state's wallet," says Prof Bhattacharya, who believed that indigenous was the way to go for this particular project.

And so he got to work with his team at IIT Kanpur in 2018. "I wanted to have a system that would be cheap, economical, indigenous and can be replicated super fast," he says about the blueprint in mind when they started developing the observatory. The process was as organic as it gets. The four sensors on the observatory include a pH sensor, a dissolved oxygen sensor, a dissolved DIC sensor and a conductivity sensor. The team had to build a filter too to get rid of the excessive sedimentation in the Ganga for the sensors to get a clear reading.

With COVID-19 scattering the workforce and travel restrictions making it difficult to import benchmark sensors from their US collaborators, the team struggled on many levels to finish the project within time. Prof Bhattacharya says that the Central Government extended support in the form of an expert panel of reviewers, who helped them through various bottlenecks, and were the reason behind this observatory being an open-source structure that can accept additional sensors and technology developed to study the river.

Completing the project within the assigned budget of around Rs 20-30 lakh was another challenge that the team had to overcome. The ground rules that the team set up in order to meet that challenge was to avoid purchasing anything off-the-shelf and instead develop their own alternatives, right from the buoy on which the observatory stands today, to the sensors that transmit real-time information on the pollutants in the river to the LoRaWAN protocol that transmits the data to the cloud.

"We did not purchase sensors, but procured transducers, which are the raw elements that go in the sensor. We fabricated the sensor along with the electronics that power it," shares Prof Bhattacharya. Then, there is the energy system that powers the observatory. A cool bit of technology that was later patented by the team, the power for the observatory is supplied via a vortex-induced vibrator. Lighting up an observatory that is essentially marooned in the middle of a river without a stable flow rate was always going to be a challenge.

"We had to devise a unique system of harnessing energy. The vortex-induced vibrator creates a vortex on the downstream that creates vibrations and then, a system converts physical energy into electric energy, which recharges the system continuously," the Prof shares, adding that the system took care to not harm marine life, as it is not based on the turbine system that can be disruptive to aquatic life.

The applications of this technology are already being felt in the mangroves of Eastern India, where the Prof says the conductivity sensor can help measure the salinity in the water. However, the professor says that the real application of the technology would be to create a network of observatories and broadcast the data for all to see. "That would help people understand the extent of pollution in the river and raise awareness on the need to keep it clean," says the professor.