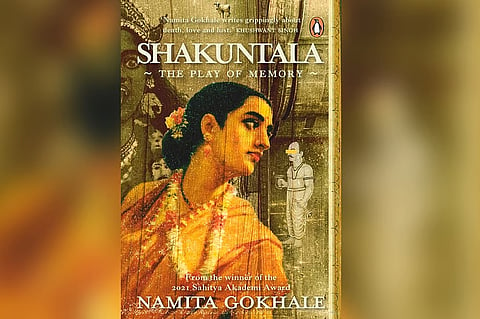

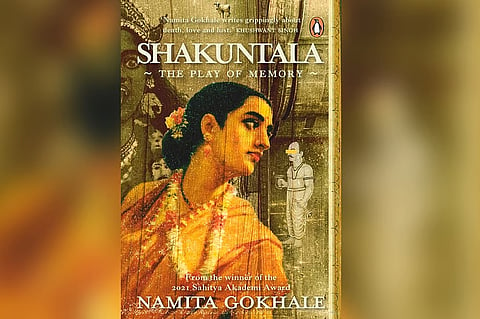

There’s a particular silence that falls over Banaras just before dawn — the river holds its breath, and the city listens to itself. That silence, heavy with centuries of faith and fatigue, is the mood Namita Gokhale catches in Shakuntala: The Play of Memory.

This is not a myth retold; it is a woman remembered. And through her remembering, the city itself begins to speak, the ancient Banaras of death and renewal, of story and superstition, of women who remember what the world prefers to forget.

The city that made me

I have always tried to read Banaras, in books, in poems, in silences. But before I could read it, the city had already read me. I arrived here as an undergraduate student at BHU, raw, unsure, carrying more questions than language. Banaras became a teacher, its alleys, lessons in humility; its ghats, meditations on impermanence. The river taught patience, and the sadhus, irreverence.

Writers have been returning to Banaras for generations, each finding a different truth buried in its light and dust, Kabir’s river of words, Tulsidas’s moral cosmos, Premchand’s ethical grime, Shiv Prasad Singh’s luminous Neela Chand, Kashi Nath Singh’s restless Kashi Ka Assi, Vyomesh Shukla’s fiery Aag Aur Paani. There is the intellectual unease of Pankaj Mishra’s The Romantics, and the lyrical ambivalence of Raja Rao’s On the Ganga Ghat. And in verse, Kedarnath Singh gave Banaras its most intimate metaphors, of clay lamps, rain-soaked mornings, and the ache of departures.

Gokhale has joined that long caravan of voices. Her Shakuntala doesn’t merely visit Banaras; it breathes it, questions it, inhabits its pulse. Through her, the city becomes not just geography but memory, a place that holds both forgetting and forgiveness, where every prayer sounds faintly like the act of remembering.

Shakuntala reimagined

Gokhale’s book traces the life of a woman who refuses to be confined by the expectations of her time. Neglected as a child and denied learning, Shakuntala seeks wisdom through wandering and introspection. Her marriage to the gentle merchant Srijan brings affection but not fulfilment, childlessness and solitude deepen her sense of incompleteness. When Srijan returns with another woman, she leaves in quiet rebellion and finds love with a Greek trader, Nearchus, in Kashi. Yet even this love cannot anchor her restless spirit. Pregnant and yearning for freedom, she crosses the Ganga alone, only to meet a tragic end. The novel’s heartbreak lies not merely in her death, but in the silencing of a woman who dared to think, desire, and defy.

The name Shakuntala comes freighted with mythology, Kalidasa’s lost-and-found heroine, the woman who waits for recognition, her story written in longing and erasure. But Gokhale’s Shakuntala has no patience for waiting. She walks out of legend and into the clutter of life, flawed, curious, tenderly rebellious, modern in spirit though tethered to old griefs that refuse to fade.

Gokhale unseals her from scripture and lets her breathe, allowing myth to collide with memory, and memory with the mundane. The novel moves between Himalayan mists and the smouldering ghats of Banaras, but its truest landscape is remembrance, that slippery country between dream and recall. Gokhale writes like someone tracing old scars under candlelight, each touch revealing a story, a hesitation, a wound. Memory here isn’t gentle; it bleeds, heals, and bleeds again, the way love does when it refuses to die quietly.

Myth, memory, and the woman’s voice

What Gokhale achieves, with remarkable subtlety, is to unfasten the myth from its patriarchal bindings. Her Shakuntala refuses to wait for recognition; she names herself before anyone else does. In her voice lies every silenced woman, the ones sanctified into forgetting. Gokhale’s Shakuntala is not rebelling for rebellion’s sake; she is remembering what was taken, claiming the right to her own memory. It is a quiet, devastating act.

The novel thus becomes more than a retelling; it is a reclaiming. It asks what stories do to women, how they make symbols of their silences. Through Gokhale’s gaze, the ancient myth becomes a mirror held to modern times.

The pulse of Banaras

In Gokhale’s Banaras, the air itself seems to shimmer with unfinished sentences. The river is a character, not a backdrop. It watches, it remembers, it forgives nothing. The ghats are both stage and graveyard, where stories end and begin again.

She writes with an eye trained in the textures of the city, the sound of temple bells at twilight, the handprint of ash on a pilgrim’s forehead, the rustle of women’s gossip by the water. Banaras in Shakuntala isn’t exotic; it’s exhausted, enduring, human.

And that, perhaps, is why I find myself drawn again to this book. Having lived my formative years here, I know that Banaras is not merely a place but a way of thinking, layered, looping, unwilling to forget. Gokhale understands that. Her Banaras holds both the noise of marketplaces and the ache of metaphysics.

The writing

Gokhale’s prose balances lyricism with lucidity. She can turn a description into a psalm, but she also knows when to cut a sentence down to the bone. The result is writing that feels lived, as if someone is whispering an old story while the world burns quietly in the background.

At times, her moral urgency jostles the poetry, but even then, sincerity steadies the hand. The novel’s power lies not in its mythic scope but in its moral hum — that soft, persistent note of empathy.

A river between two times

Like the river Ganga that threads through the story, Shakuntala moves between the mortal and the mythic, the remembered and the lost. The city’s rituals of death and renewal mirror the book’s own preoccupation, that to remember is to be reborn, and to forget is only another form of living.

The novel ends like a conch sound fading over the river, unfinished, resonant, alive. Gokhale does not seek resolution; she offers something rarer: continuity. Her Shakuntala stands not in the shadow of Kalidasa’s creation, but beside her, speaking, finally, in her own voice.

Shakuntala: The Play of Memory is among the finest literary meditations on Banaras in recent memory, luminous, intimate, unhurried. It reminds us that the city, like memory, can never be contained, only revisited, each time with a different ache. For me, reading it was like walking again by the river at dusk, where light touches water, and everything, for a moment, remembers itself.

(The author writes regularly on society, literature, and the arts, reflecting on the shared histories and cultures of South Asia.)