"He gazed sadly at the threatening sky, at the burned-out remnants of a locust-plagued summer, and suddenly saw on the twig of an acacia, as in a vision, the progress of spring, summer, fall and winter, as if the whole of time were a frivolous interlude in the much greater space of eternity, a brilliant conjuring trick to produce something apparently orderly out of chaos, to establish a vantage point from which chance might begin to look like necessity..."

"Death, he felt, was only a kind of warning rather than a desperate and permanent end."

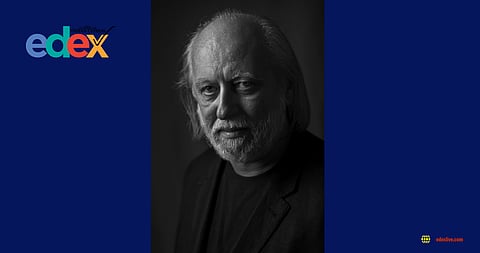

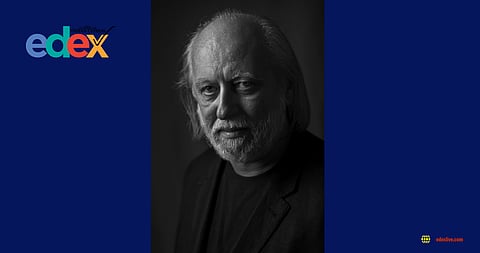

After the news broke that Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai had won the Nobel Prize in Literature, I scoured through my Gmail drafts and found these passages from Satantango—two lines I had once saved and that now resurfaced with renewed meaning.

I felt compelled to share this as a glimpse into the depth and intensity of Krasznahorkai's remarkable prose.

"So, at last, the inimitable Krasznahorkai has won the Nobel Prize in Literature," I sighed. I say "at last" because for writers like him such an honour has long been overdue.

Doris Lessing won the award at 87. Krasznahorkai is only 71.

In these times of social media saturation, artificial intelligence, and global catastrophe, voices like Hemingway, Kafka, Beckett, and Krasznahorkai — and those in their lineage — are rare and precious. They illuminate the bleakness of existence — not to overwhelm us, but to remind that even amid despair, a fragile thread of hope can still be found.

I was hooked on Krasznahorkai after reading Satantango (1985), his bleak and mesmerising debut, later adapted into a haunting film by Béla Tarr.

Since then, I’ve read two more of his works: The Last Wolf and Herman (2017), a pair of novellas exploring isolation and moral exhaustion, and Seiobo There Below (2013), a meditative collection of stories bound by themes of art, beauty, and spiritual devotion.

Satantango is a funny but dark work. The elements and landscape reflects the despondent lives of the people who witness a miracle only to discover that there are no miracles.

In the novel, the agonising wait of peasants in a Hungarian village after the machines had long ceased in the collective farm ends with the arrival of their executioner, Irimias, and his aide, who exploit and lead them towards their death.

In fact, the arrival of Irimias bring them hope a "real golden age," and they fall for the trap. Like a herd of sheep they follow the shepherd (no more the good shepherds) to the slaughter house.

Seiobo There Below and The Last Wolf and Herman are daunting reads but worth the time spent. Seibo draws from the author's extensive travels in China and Japan while Wolf is about the hunting of wild animals. The latter contains a single sentence lasting 70 pages.

Hari Kunzru wrote in The Guardian about Seiobo: "From the first story, a bravura account of the consciousness of a crane standing in the Kamo river in Kyoto, the reader kayaks down Krasznahorkai’s torrential sentences through biblical ancient Persia, as queen Vashti refuses to appear before her drunken husband, into a temple in a Japanese industrial town where a statue of Amida Buddha is removed, driven to Tokyo, painstakingly restored and then returned, amid much ceremony..."

I don't keep a diary. I jot down my thoughts on my phone. Along with the passages from Satantango, I stumbled upon these lines I have jotted down about my favourite authors.

What will poet Blake tell Jesus if they met in a desert?/ OV Vijayan would be muttering Om Bhur Bhuva Swaha...Dostoevsky would be brooding at the crossroads, Eco lost in the labyrinth of a library, Borges seeking paradise, Coetzee alone and silent lost in meditation & Krasznahorkai pondering over his next dystopian and melancholic work.

The Nobel Prize hailed Krasznahorkai "for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”. He "also looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone. The result is a string of works inspired by the deep-seated impressions left by his journeys to China and Japan."

Krasznahorkai's name has long circulated among critics as one of the most original in European fiction—a writer of vast, hypnotic sentences exploring dark and philosophical themes.

Critics see shades of Samuel Beckett in Krasznahorkai.

He won the Man Booker International prize 2015.

The judges there said, "In László Krasznahorkai's The Melancholy of Resistance, a sinister circus has put a massive taxidermic specimen, a whole whale, Leviathan itself, on display in a country town. Violence soon erupts, and the book as a whole could be described as a vision, satirical and prophetic, of the dark historical province that goes by the name of Western Civilisation."

According to the Man Booker website, he is known for his difficult and demanding novels, often labelled postmodern, with dystopian and melancholic themes.

Krasznahorkai has won numerous prizes, including the 2013 Best Translated Book Award and the 1993 Best Book of the Year Award in Germany.

He first shot to recognition in 1985 when he published Satantango, which he later adapted for the cinema in collaboration with the filmmaker Bela Tarr. In 1993, he received the German Bestenliste Prize for the best literary work of the year for The Melancholy of Resistance.

Krasznahorkai and his translator George Szirtes were longlisted for the 2013 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for Satantango and Krasznahorkai has won the Best Translated Book Award in the US two years in a row, in 2013 for Satantango and in 2014 for Seiobo There Below.

The Hungarian master once described his writing style as "reality examined to the point of madness". The great American writer Susan Sontag called him the "master of the apocalypse".

Krasznahorkai has also spoken elsewhere of his quest to be an "absolute original" and "not make some new version of Kafka or Dostoyevsky or Faulkner".

The 2025 Nobel restores faith in the Prize, celebrating a true master of his craft.

[Article by Gladwin Emmanuel of The New Indian Express]