Can you imagine a childhood devoid of storybooks? All those brightly coloured pictures of flowers, fun sketches of baby elephants and kangaroos, talking trains and buses and all the sweet little stories. They really do bring a smile, don't they? These books shape our first and most crucial years of learning. And yet, an entire section of children grow up without ever reading a story in their lives. For a visually-impaired child, the first book that they ever hold is their first-grade textbooks. But Chetana Trust has been trying to change the endings of these pictureless stories. The Trust designs books for differently-abled children and they also run a library to make these books more accessible to them.

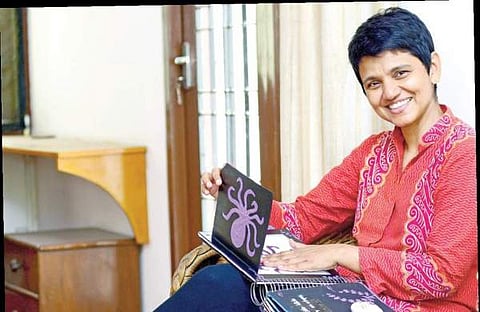

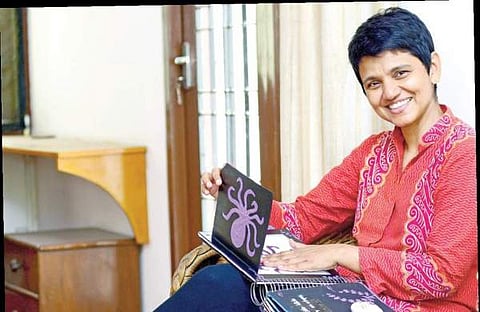

Namita Jacob, the Director of Chetana Trust, noticed how her colleague's child, who was only a few months old was so engrossed in a picture book. "That's when it struck me that children start to grasp colours and words at such a young age. By not having access to storybooks, differently-abled children are losing out on such an important and influential aspect of their lives," she says. Chetana brought out their first book in the early 2000s that were designed for toddlers with visual impairment or intellectual disabilities.

"Strangely though, a 12-year-old student of mine called me up and gave me an earful about why I hadn't informed her about the book release. I couldn't understand why she wanted a book designed for toddlers," Namita recalls. That's when the child told her, "My amma tells me stories from her childhood and reads to me from her childhood books. Now, I also have a book that I can read to my children, whenever I have them."

Namita received a similar reaction from a visually-impaired reviewer to whom she had given the book for feedback, "The reviewer did not want to return the book. They wanted to keep it because it was the first time they could actually read a children's book, even though they were adults now. A lot of differently-abled adults enjoy these books as much as children," she says.

So how are these books designed? For children with complete visual impairment, the storybooks are produced in braille. For children with partial eyesight, the pictures are bigger and the font is also larger. For children with intellectual disabilities, the language used in the stories is simplified, using smaller words, shorter sentences and based on real objects that the child can identify. For children with cerebral palsy, even turning a page of a book is an impossible task. To tackle this problem, the storybooks are designed like how our old Yellow Pages were once designed (different letters have a different cut at the end of the sheet). The books are also made with on hardboard so that it is easy to turn. Besides these, Chetana also has to take into consideration children with more than one kind of disability. Differently-abled children are usually passive consumers of stories, but with these new books, they also became active creators of stories.

Chetana has tied up with Tulika Publishers, which features differently-abled characters and seeing characters like themselves in these books gives these kids a real thrill. "It's not that the children identify with the disability, but they look for similarities in the way that other characters react or what activities the disabled characters indulge in. Once a child told me how she was thrilled to find the character in the book also had similar parents who went on telling her what to do. Another kid was bewildered to find a child in a wheelchair zooming around the city, hunting for a missing cat," Namita recalls.

But the most unexpected consequence of this experiment has been the impact it has had on parents, she says, adding, "The disability is not the biggest obstacle for a child; it's the lack of belief, inspiration and dreaming capabilities in the adults who surround them. Adults don't seem to see a regular life for their child. So, when they see characters in books climbing trees or going to the beach or laughing, they are pleasantly surprised."

Since the team has not yet come up with a solution to mass produce these books, the children use the library for now. "I'm not so stressed about mass producing these books because we have quite a reach. A child gets two books a month and we also invite storytellers to borrow our books. The library is a year old. When we first ask these children what their favourite hobbies are, they say swimming or music or colouring, but now for the first time, the kids say that they love reading. That itself is a great achievement," she explains.

Before the library was set up, Namita was known as the 'bag lady' because she would carry around a bag full of books and distribute it in facilities that cater to these children. "People would ask me how I leave the books with the kids since there is a risk of them getting ruined. I've been doing this for years, there are less than five books that have been misplaced or returned in bad condition," she states.

The question of scaling up the initiative is a recurring thought for Namita, who is now expanding to Delhi and Bengaluru. But then she goes on to say something interesting about the people who volunteer with her, "I have an old lady who is dying of cancer, a young woman who is terminally ill, a couple who are depressed about their dead son, adults who are disabled, retired teachers and people with various mental illnesses. Working for young disabled children gives their life meaning."

"We can of course work on making machines that can produce these books, but what we can also do is go into our prisons, into hospitals with terminally ill patients. These people can help create these books. It's a win-win situation as it acts as a healer for them too. Our population is both a weakness and a strength. Mass producing is possible, but let's try it without machines first," concludes Namita, confidently.